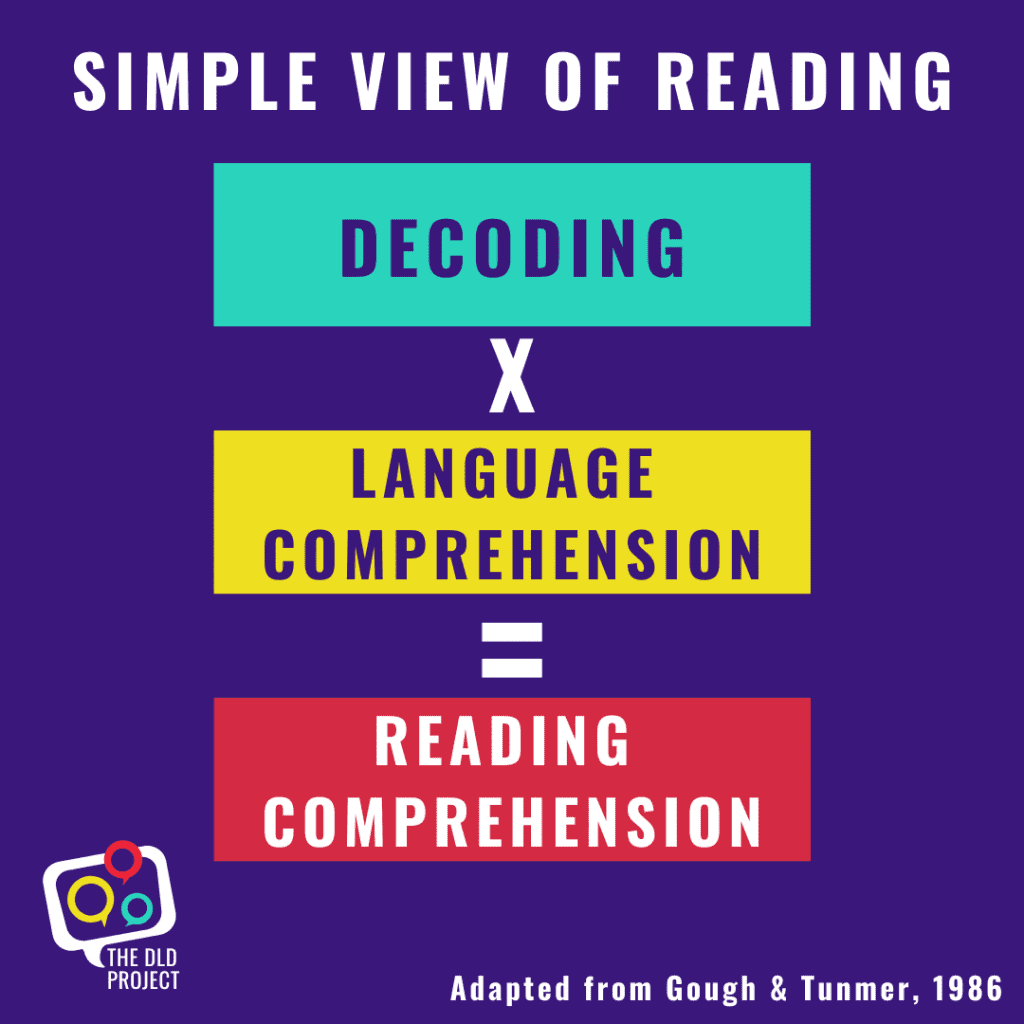

Many children with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) can struggle with letter-sound knowledge and understanding language. Both are critical skills in reading for meaning! Explicit learning of letter-sounds can occur through a systematic synthetic approach to phonics, however families often tell us that supporting their child’s understanding of what’s happening in the story can be tricky. So we’ve reached out to our friend, Tania and Janice, who are speech pathologists and owners of Little Birdie Books to put together their tips and tricks to help at home (or school).

“On went the mouse through the deep, dark wood,

A snake saw a mouse and the mouse looked good.

Where are you going to little brown mouse?

Come for a feast in my log pile house…”

Sound familiar? Yes, it is the captivating rhyme found in the ‘The Gruffalo’ by children’s book author, Julia Donaldson. This best-selling narrative, like many other great picture books, is filled with opportunities for children to develop their inferencing skills. But, just as the books don’t read themselves, nor will your child develop strong inferencing skills independently. Instead, this crucial skill is planted, grown and pruned in the laps of parents.

Let’s take a closer look at what experts are calling the ‘hidden language skill’, inferential comprehension…

WHAT IS INFERENCING?

An inference is a conclusion or opinion that relies on drawing from existing knowledge, facts, evidence or experiences. The word ‘infer’ comes from the Latin prefix in- meaning ‘into’ and the Latin base word -ferro meaning ‘to carry’. Therefore, to infer, means to ‘carry forward’ or go beyond what has been explicitly presented.

Sometimes referred to as ‘reading between the lines’, the reader must use their background knowledge (experiences, topic, vocabulary, text structure) combined with text information to make an ‘inference’. In other words, the author has implied rather than stated something in the story and the reader must then infer the meaning. In the example of The Gruffalo, the author has implied that the snake is tricking the mouse and rather than wanting to have a lovely feast with him, he wants to feast on him. Drawing on one’s background knowledge that snakes like to eat mice (and that snakes are often depicted as ‘sneaky’) is certainly useful information when inferring the meaning of the snake’s words.

THE ROLE OF READ ALOUDS

Read-alouds can be an ideal context for engaging children in sustained conversations or ‘shared thinking’ with an inferential focus. If children are to be empowered to use language for thinking and understanding, they need to develop abilities to operate at an inferential level (Lennox, 2013). So as a ‘Speechie Mum’ I am inspired to share my learnings about the value of inferencing as a key contributor to reading, school and lifelong success.

Here are 5 actionable tips to support your child (younger or older) to develop the high level language skill of inferencing:

#1 Assumption makes an ass out of you and me

It is very easy as adults to forget that children may not be piecing the puzzle together accurately as you read. Think about the famous story of ‘The Three Billy Goats Gruff’. Even though this story appears basic, three goats make a plan to cross the bridge to eat the greener grass, there are implied messages that make the narrative more complex.

Using a ‘think aloud’ comment to explain the part of the story not explicitly stated is essential. For example, “Oh so the Middle Billy Goat Gruff tricked the Bad Old Troll into letting him cross the bridge without being eaten. This happened because the Bad Old Troll was being greedy and wanted to eat the biggest Billy Goat Gruff ”

#2 Pauses between pages are powerful

Reading aloud is best done as a conversation. Researchers call this ‘dialogic’ or shared reading and neuroscientists from Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University reinforce the importance of ‘serve and return’ conversations for language development. Many well-meaning parents will diligently read stories aloud every night but forget to turn reading into a conversation. It is the strategic pauses where your child may start a conversation or ask a question that helps to build that serve and return conversation. But, if they don’t take a turn, you can always pause then say something casual like “Hang on, what’s happening?” or “OK so what has happened so far?”. It continues to blow me away when I think my child has understood the story and then I realise they have completely missed the mark.

#3 Judge a book, just not by its cover

When it comes to pictures books, not all picture books are created equal. Selecting the right book contributes to successful read-alouds; the repertoire should include a variety of well-illustrated, quality literature. Use stories containing well-defined story structure, higher level vocabulary and emotions, whilst providing exposure to literate language (Westerveld & Gillon, 2008). Half the battle is finding the engaging books to read aloud that are enjoyable for adults and children. Little Birdie Books painstakingly scours the world of picture books for stories that are both language-rich and engaging for children 3-6 years of age…and their parents.

#4 On the road but not in the lane

McKeown and Beck (2007) used the term ‘‘on the road, but not in the lane’’ when referring to children’s responses to inferential question that were close but not quite. I think we can all agree that some evenings all we have left in the tank in response to our child’s remarks about the story is an “Oh right” then turn the page. But the researchers maintained that parents and educators need to follow up children’s responses with prompts for elaboration such as why, how or “tell me more”. This kind of talk is much more complex than shallow turn-taking (McKeown and Beck, 2007).

#5 Train your ‘mini-apprentices’

van Kleek et al. (2006) suggest that adults can model inferential thinking skills and scaffold children’s language, thus providing an apprenticeship in skills which children will later use independently. Modelling for comprehension is simple. Just pretend out loud that you are figuring out the story, problem, characters’ emotions and motives and the potential solutions. Essentially you are demonstrating purposeful pauses, ‘working it out’ thinking, lots of sabotage (“I’m confused”), making thought-provoking comments and questions and elaborating on your child’s responses. Oh and don’t forget these apprenticeships can last for years, well beyond when your child learns to read to themselves. The message?

Never. Stop. Reading. Aloud.

LET’S ARMOUR UP!

If children are to be empowered to use language for thinking and understanding, they need to develop abilities to operate at an inferential level.

This requires the readers (parents, grandparents and educators) to go beyond information directly presented in the text and illustrations. Let’s encourage children to use language for critical thinking where children practise wondering, exploring, imagining, predicting, pondering, explaining and analysing.

We have a unique window of opportunity in children’s lives to capitalise on inferential comprehension when the app has not yet replaced the lap. Give your child the armour they need to protect themselves against challenges in communication, reading and academia. What you say matters!

By Tania and Janice | Little Birdie Books

Speech Language Pathologists

REFERENCES

Center on the Developing Child (2020) Serve and return. Cambridge: MA: Center on the Developing Child. Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/serve-and-return (accessed Otober 2021).

Dawes, E. Leitão, S., Claessen, M. (2019) Oral literal and inferential narrative comprehension in young typically developing children and children with developmental language disorder, International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 21 (3), 275-285. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2019.1604803

Dawes, E., Leitão, S., Claessen, M., & Kane, R. (2018). A profile of the language and cognitive skills contributing to oral inferential comprehension in young children with developmental language disorder. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(6), 1139-1149. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12427

Dawes, E. (2017). The hidden language skill: oral inferential comprehension in children with developmental language disorder. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11937/56528

Greenberg, J. & Weitzman, E. (2014).I’m Ready!™ How to Prepare Your Child for Reading Success . Toronto, Ontario: Hanen Early Language Program.

McKeown, M., & Beck, I. (2007). Encouraging young children’s language interactions with stories. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (Vol. 2, pp. 281–294). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Uccelli, P., Demir‐Lira, Ö. E., Rowe, M. L., Levine, S. and Goldin‐Meadow, S. (2018), Children’s Early Decontextualized Talk Predicts Academic Language Proficiency in Midadolescence. Child Development. E-publication ahead of print: doi:10.1111/cdev.13034.

van Kleeck, A., Vander Woude, J., & Hammett, L. (2006). Fostering Literal and Inferential Language Skills in Head Start Preschoolers with Language Impairment Using Scripted Book-Sharing Discussions. American Journal of Speech – Language Pathology, 15, 85-95.

Weitzman, E. & Greenberg, J.(2010).ABC and Beyond™: Building Emergent Literacy in Early Childhood Settings. Toronto, Ontario: Hanen Early Language Program.